Sometimes people do not read footnotes in texts.

I do. Garrigou-Lagrange has these three in his section on the Illuminative State, which I think will be helpful for all of us. Garrigou-Lagrange's next chapter highlight St. Catherine and Bl. Henry, and here are some of his extensive points. My boldface type highlights.................

8. In the prologue of his Rule, St. Benedict wrote: "Let us therefore at length arise, since the Scriptures stir us up, saying: 'It is now the hour for us to rise from sleep' (Rom. 13:11). And our eyes being now open to the divine light, let us hear with wonderment the divine voice admonishing us, in that it cries out daily and says: 'Today if you shall hear His voice, harden not your hearts.' " That is to say: It is time to rise from the sleep of negligence and to walk courageously in the way of God.

Garrigou-Lagrange rightly and clearly expresses that the Illuminative State is a second conversion. This waking up is absolutely a gift from God, but one has to cooperate with this.

It does not happen if one is NOT ORTHODOX and if one is orthodox and falls away from the Church, the Illuminative State ends in heresy and condemnation. Now, one may be "outside" the Catholic Church and receive great graces for the very purpose of God calling one to become Catholic. This can be a painful decision.

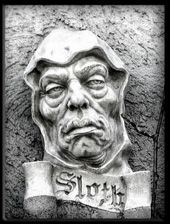

One falls because of pride, mostly, and stupidly thinking that one is arriving at these stages by one's own efforts and not by grace.

9. We shall see farther on that, as St. Catherine of Siena says in her Dialogue (chaps. 60, 63), the second conversion of the apostles took place more properly at the end of the Passion when Peter wept over his denial, and that Pentecost was like a third conversion or more properly a transformation of the soul, which marks the entrance into the unitive way.

This is absolutely spot on.

Garrigou-Lagrange should be canonized. His insights as to Catherine of Siena's Dialogue, a book I recommend to all, shows that Catherine received graces for the Unitive Way, which I have not discussed yet.

One cannot enter the Illuminative State without purgation and one finishes purgation in the Illuminative State.

No pain, no gain. Sorry, but the Protestants miss this point by insisting that a sign of election is wealth. Nope.

I shall write about the Third Transformation when I have exhausted the Illuminative State explanations. I have never personally met a living man, woman or child in the Unitive State, although I have met several in the Illuminative State. Age, by the way, does not matter. Catherine died at 33.

Here is G-L on her contribution: Christ is speaking to Catherine.

We read in chapter 60: "Some there are who have become faithful servants, serving Me with fidelity without servile fear of punishment, but rather with love. This very love, however, if they serve Me with a view to their own profit, or the delight and pleasure which they find in Me, is imperfect. Dost thou know what proves the imperfection of this love? The withdrawal of the consolations which they found in Me, and the insufficiency and short duration of their love for their neighbor, which grows weak by degrees, and oft-times disappears. Toward Me their love grows weak when, on occasion, in order to exercise them in virtue and raise them above their imperfection, I withdraw from their minds My consolation and allow them to fall into battles and perplexities. This I do so that, coming to perfect self-knowledge, they may know that of themselves they are nothing and have no grace, and, accordingly in time of battle fly to Me as their benefactor, seeking Me alone, with true humility, for which purpose I treat them thus, withdrawing from them consolation indeed, but not grace. At such a time these weak ones of whom I speak relax their energy, impatiently turning backward, and so sometimes abandon, under color of virtue, many of their exercises, saying to themselves: This labor does not profit me. All this they do, because they feel themselves deprived of mental consolation. Such a soul acts imperfectly, for she has not yet unwound the bandage of spiritual self-love, for had she unwound it, she would see that, in truth, everything proceeds from Me, that no leaf of a tree falls to the ground without My providence, and that what I give and promise to My creatures, I give and promise to them for their sanctification, which is the good and the end for which I created them."

and again,

In chapter 63 of The Dialogue, the saint says, in speaking of the passage from mercenary to filial love: "Every perfection and every virtue proceeds from charity, and charity is nourished by humility, which results from the knowledge and holy hatred of self, that is, sensuality. . . . To arrive thereat. . . a man must exercise himself in the extirpation of his perverse self-will, both spiritual and temporal, hiding himself in his own house, as did Peter, who, after the sin of denying My Son, began to weep. Yet his lamentations were imperfect, and remained so until after the forty days, that is, until after the Ascension. But when My Truth returned, to Me in His humanity, Peter and the others concealed themselves in the house awaiting the coming of the Holy Spirit, which My Truth had promised them. They remained barred in from fear, because the soul always fears until she arrives at true love. But when they had persevered in fasting and in humble and continual prayer, until they had received the abundance of the Holy Spirit, they lost their fear, and followed and preached Christ crucified."St. Catherine of Siena shows in this passage that the imperfect soul which loves the Lord with a love that is still mercenary, ought to follow Peter's example after his denial of Christ. Not infrequently this time Providence permits us also to fall into some visible fault to humiliate us and oblige us to enter into ourselves, y at as Peter did, when immediately after his fall, seeing that Jesus looked at him, he "wept bitterly." (1)

And more, and a warning: this second conversion is not obvious, nor is it necessarily "charismatic".

The second conversion may also take place, though we have no grave sin to expiate, for example, at a time when we are suffering from an injustice, or a calumny, which, under divine grace, awakens in us not sentiments of vengeance, but hunger and thirst for the justice of God. In such a case, the generous forgiving of a grave injury sometimes draws down on the soul of the one who pardons, a great grace, which makes him enter a higher region of the spiritual life. The soul then receives a new insight into divine things and an impulse which it did not know before. David received such a grace when he pardoned Semei who had outraged and cursed him, while throwing stones at him.(3)

This has been in my experience and forgiveness opens the door to grace. But, this

"yes" opens the door to great suffering as well.

A more profound insight into the life of the soul may originate also on the occasion of the death of a dear one, or of a disaster, or of a great rebuff, when anything occurs which is of a nature to reveal the vanity of earthly things and by contrast the importance of the one thing necessary, union with God, the prelude of the life of heaven.

In her Dialogue St. Catherine also speaks often of the necessity of leaving the imperfect state in which a person serves God more or less through interest and for his own satisfaction, and in which he wishes to go to God the Fatherwithout passing through Jesus crucified.(4) To leave this imperfect state, the soul which still seeks itself must be converted that it may cease to seek itself and may truly go in search of God by the way of abnegation, which is that of profound peace.

There is no short-cut.

Staying with the Dominicans today, on the Feast of the Greatest, I pick up on G-L's reference to Henry Suso, who I first discovered in about 1980. Here is a section of his writings to help us. Again, read footnotes, as they are good for you! They led up to the following chapter.

10. For example, the second conversion of Blessed Henry Suso, of St. Catherine of Genoa, of Blessed Anthony Neyrot, O.P., and of many others, is well known.

The works of Blessed Henry Suso contain a number of instructions relative to the second conversion. He himself experienced this conversion after a few years of religious life, during which he had slipped into some negligences. Particular attention ought to be given to what he says about the necessity of a more interior and deep Christian life in religious who give themselves most exclusively to study, and in others who are chiefly attentive to exterior observances and austerities. In the divine light he saw "these two classes of persons circling about the Savior's cross, without being able to reach Him," (5) because both groups sought themselves, either in study or in exterior observances, and because they judged each other without charity. He understood then that he should remain in complete self-abnegation, ready to accept all that God might will, and to accept it with love, at the same time practicing great fraternal charity. (6)

Do not circle the Cross. Embrace it.

And I end with a helpful footnote and also section on St. Thomas Aquinas.......

15. This mode of acting conforms perfectly to what St. Thomas says of the difference between acquired prudence (a true virtue, already described by Aristotle) and infused prudence. and the gift of counsel (IIa IIae, q.47, a.14 and q. 52). Should a man tend to perfection under the almost exclusive direction of acquired prudence (which is, nevertheless, not that of the flesh), he would never reach true Christian perfection, which belongs to the supernatural order; such perfection requires the frequent exercise of infused prudence and of the gift of counsel. These three sources of actions (habitus) are among themselves a little like what agility of the fingers, the acquired art which is in the practical intellect, and musical inspiration are in the musician. Without art, properly so called, and this inspiration, a man will certainly never produce a masterpiece, and will never be able even to comprehend one.

And, so that we do not become full of pride, God allows us to fall......

In connection with Peter's second conversion, we should recall that St. Thomas teaches (2) that even after a serious sin, if a man has a truly fervent contrition proportionate to the degree of grace lost, he recovers this degree of grace; he may even receive a higher degree if he has a still more fervent contrition. He is, therefore, not obliged to recommence his ascent from the very beginning, but continues it, taking it up again at the point he had reached when he fell. A mountain climber who stumbles halfway up, rises immediately, and continues the ascent. The same is true in the spiritual order. Everything leads us to think that by the fervor of his repentance Peter not only recovered the degree of grace that he had lost, but was raised to a higher degree of the supernatural life. The Lord permitted this fall only to cure him of his presumption so that he might become more humble and thereafter place his confidence, not in himself, but in God. Thus, the humiliated Peter on his knees weeping over his sin is greater than the Peter on Thabor, who did not as yet sufficiently know his frailty.

To be perfect is to be conformed to Christ. We become like Him. We are His Face in the world...........